Blowouts are rare, but when they do happen they can destroy well equipment, damage the environment and in extreme cases kill the crew working on the well. If the well’s surface equipment is destroyed or damaged by a blowout (the force of flow can eject the drill pipe from the well, damage the blowout preventer (BOP) or even catch fire and destroy the rig), it is often possible to remove damaged wellhead equipment and replace it with new equipment that has a valve that can be closed. This is a dangerous and messy process, but many wells have been controlled by installing a new valve at the surface and then closing the valve. In extreme cases, an alternative is to drill a relief well to intersect the damaged well in the subsurface in order to control the flow.

Whether accessing the well through its own BOP or through a relief well, there are a variety of methods to bring the well back into operational control. This discussion explains the operations termed as top kill, bottom kill, static kill and dynamic kill.

Top vs Bottom Kill

Top and bottom kill are related to where the kill fluids are introduced to the blowout well. For a top kill, as suggested, the fluids are injected at the top of the well, which usually means the rig and BOP stack on the blowout well is still functional, or a well-control crew has replaced damaged equipment with a new BOP and manifold to allow access to the wellbore. A bottom kill requires accessing the blowout well in the subsurface, which requires a relief well to intersect the blowout well downhole. This results in kill fluids being introduced downhole, or at the bottom of the well. We will discuss relief wells in more detail on the next page.

The mobile offshore drilling unit Q4000 (at right with several cranes and central white tower) holds position directly over the damaged Deepwater Horizon blowout preventer as crews work to plug the Macondo Well using a top kill. Discoverer Enterprise, in the foreground, was used to collect oil and gas from the damaged subsea wellhead.

Static vs Dynamic Kill

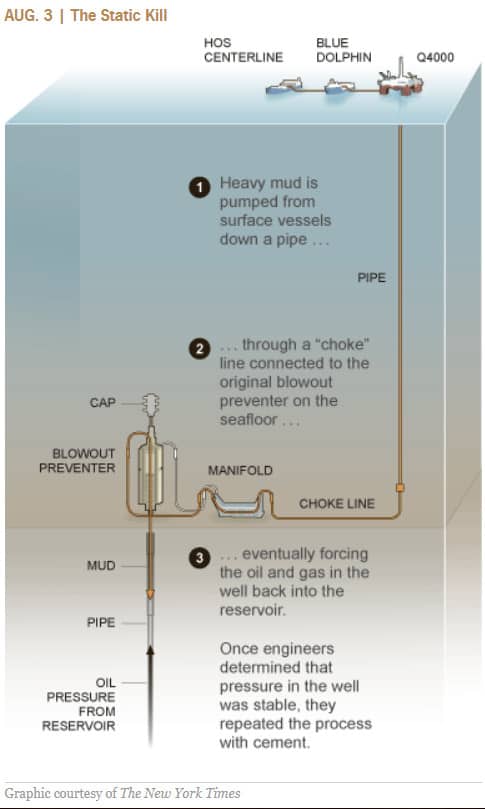

A static kill requires fluids that have a high enough density (i.e., mud weight) such that the hydrostatic pressure they exert can stop the formation fluids from flowing up the well, and the new hydrostatic pressure from the higher density fluids returns the well to a balanced or slightly overbalanced condition. The kill fluids are typically heavy drilling mud but in extreme cases might be cement. With cement, the intention is to permanently kill the well and abandon it. A challenge with a static kill is that reestablishing a higher pressure in the wellbore does not just require a high density fluid, but it requires a column of fluid of significant height. If the well is flowing out of control, it is hard to push enough kill fluid into the well, typically from the surface, in order to counteract the energy of the flow.

The mobile offshore drilling unit Q4000 successfully used a static kill on the Macondo Well.

A dynamic kill typically involves introducing heavy kill fluids downhole into the flow stream of the formation fluids causing the blowout, increasing their density and viscosity such that their flow resistance introduces enough back pressure to kill the well. Because the kill fluids flow to the surface with the formation fluids, and in a blowout these fluids are lost and not recirculated, a large volume of kill fluid is typically needed, and it needs to be introduced at a particular rate in order to have sufficient effect. The fluids for the dynamic kill can be introduced through the drill pipe (or tubing) of the blowout well (if such equipment is still operational) in a top kill fashion, or they can be pumped through an intersecting relief well, which would make it a bottom kill.

What are the two types of tertiary well control processes, “top kill” and “bottom kill,” related to?

kill fluids are introduced to the blowout well to stop uncontrolled flow

Correct.

kill fluids are introduced to the well to stimulate fractures in the rock for hydrocarbon production

Incorrect.

Neither A or B

Incorrect.

What type of well kill procedure requires accessing the blowout well in the subsurface, which requires a relief well to intersect the blowout well downhole?

Top Kill

Incorrect.

Static Kill

Incorrect.

Bottom Kill

Correct.

What type of well kill procedure involves introducing heavy kill fluids downhole into the flow stream of the formation fluids causing the blowout?

Static Kill

Incorrect.

Top Kill

Incorrect.

Dynamic Kill

Correct.

Image Credits: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Patrick Kelley, Public Domain; The New York Times, National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, Public Domain

Image Credits